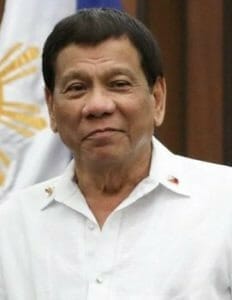

Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte placed Metro Manila under community quarantine on March 12. Two days after, on March 14, an “enhanced” community quarantine (ECQ) was imposed, putting the entire Luzon island on lockdown. The ECQ aimed to restrict the movement of the population, with the exception of medical frontliners and workers from selected government offices. It also mandated the temporary closure of non-essential shops and businesses.

The ECQ was originally scheduled to end on April 13, but with the number of Covid-19 positive cases and Covid-19-related deaths still on the rise, it was extended to April 30. Less than a week before the already extended ECQ’s lifting, Duterte imposed another extension, this time with an even stricter implementation and with threats of imposing Martial Law.

As of this writing, April 25, there are 7,294 Covid-19 positive cases and 446 deaths in the Philippines. The country’s figures, according to experts, have made the Philippines one of the worst-hit in Southeast Asia. Yet these numbers have been highly contested by health advocacy groups. They argue that the relatively low number of recorded cases may be due to the lack of mass testing efforts, which only began on April 14 – a month after the ECQ was declared.

Filipinos are penniless and hungry, many medical professionals at the frontlines are getting sick or have died, and mass testing has yet to be made available to the most vulnerable.

More than a month after the start of the lockdown, it remains unclear whether the measure has really “flattened the curve.” What is sure is that countless Filipinos are penniless and hungry, many medical professionals at the frontlines are getting sick or have died, and mass testing has yet to be made available to the most vulnerable. To date, most efforts to raise funds to support health professionals and distribute aid can be credited to grassroots organizations, the private sector, and groups of individuals who have acted on basic common sense and compassion.

Duterte, who is almost always surrounded by military men in his weekly addresses, and who has put military men in charge as members of the National Taskforce Against Covid-19, finally, but rather belatedly, met with health experts on April 20. He initially offered a Php 10 million (USD 197,000) reward for anyone who can discover a vaccine for Covid-19 and then increased the prize money to Php 50 million on April 24. So much for a scientific approach to fight a pandemic and actual funding for health R&D be damned.

With mounting cases and deaths despite the lockdown, the Duterte government is scrambling and trying to find something or somebody to blame — except itself. As it clumsily plays the blame game, the Philippine government has repeatedly refused to recognize weaknesses in its handling of the pandemic, and even persists in repeating its mistakes. This blaming-everyone-but-oneself strategy is consistent with Duterte’s policies and leadership style since he was elected in 2016.

Forcing and shaming into obedience

Duterte makes every effort to distract the increasingly angry and frustrated public.

The Duterte government has not provided scientific and evidence-based explanations for the measures it has taken and for actions it wants the public to take. Instead, it has forced people into obedience and shamed those whom it accuses of non-obedience. This is reflected in government propaganda: from statements made by the president and officials closest to him to mainstream media commentators, all the way to social media “influencers” and paid trolls.

When he declared the lockdown on March 12, he called on the public to “just obey” the the authorities and the government. In social media, paid trolls virulently attacked critical reactions to the speech. They claimed that critics do fail to understand the president. One of their mantra was that the Philippines does not have the worst government, but it does have the worst citizens. Subsequently, Duterte, in another televised speech, commanded the public to just “follow orders.” As if on cue, paid social media trolls repeated the message – “sumunod ka na lang” – in reaction to innumerable complaints about the lockdown’s chaotic implementation and the seeming lack of any plan in dealing with the pandemic.

Then, the government’s messaging further shifted from coercion to outrightly blaming those who do not obey government orders for the virus’ spread. At a virtual media briefing, the presidential spokesperson himself said, “There are many pasaways in our ranks. Because of that, we are again number one in the ASEAN for the number of COVID-19 [cases]. That is shameful! Stop being pasaways. Stay in your houses.”

They need to be forced to obey, not just with words, but by the very real threat of being arrested or shot.

Some reporters have translated the Tagalog word “pasaway” as “hard-headed people.” The root word is “saway,” which means “to discipline,” and the Filipino prefix “pa-” indicates a person who needs to be disciplined. This pasaway rhetoric was echoed by a Filipino actor whose TikTok post became viral, in part thanks to paid trolls. In the post, he argues: “Why does the quarantine keep on extending? Because Filipinos are hard-headed. When told not to go out, they keep going out and when they get sick, they blame others.”

Repeated again and again by the government’s social media influencers and paid trolls, a narrative has been created wherein Filipinos are portrayed as “pasaway” and “walang disiplina” (having no discipline). They need to be forced to obey, not just with words, but by the very real threat of being arrested or shot.

In his latest televised address on April 24, Duterte repeatedly slammed the New People’s Army (NPA), the Communist-led armed rebel group in the country. Claiming that the NPA is fomenting “lawlessness” and killing indiscriminately, he called on the military to destroy the rebel group, and threatened to impose martial law nationwide. Coming one day after an ex-soldier who had Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder had been shot to death by policemen for allegedly violating quarantine restrictions, the message was taken seriously by the public.

Many observers have commented that the president’s attacks on the NPA is part of an effort to distract the increasingly angry and frustrated public. They point out that Duterte seems to want a war with the NPA, not with Covid-19 – and as if the NPA is the reason for the non-containment and spread of the virus. The president’s tirade against the NPA, however, is a continuation of its blame game for the virus’ spread.

Read: Taking on the Virus, Talking with his Fists: Duterte’s Unique Approach to the COVID-19 Crisis

Photo: junpinzon / Shutterstock.com

Why the blame game?

To lay the blame is much easier than being accountable to an increasingly angry public. Until mid-March, the Duterte government had downplayed the threat posed by the pandemic. Duterte himself issued many statements belittling the virus and the disease, making it a pretext for his jokes and using it to project his strongman image. His Health Secretary even bragged that the country is very well-prepared for the virus and has distinguished itself in dealing with the pandemic in Southeast Asia. His spokesperson promoted the fake news that bananas and gargling saltwater can cure the disease.

By mid-March, it was already too late, as a Philippine Daily Inquirer editorial said, to “fortify the creaking health system, particularly the Research Institute for Tropical Medicine; prepare hospitals as well as laboratories and other testing institutions; launch an aggressive public information campaign on the virus; and marshal personnel and resources, including, most importantly, securing test kits for the teeming population.”

It was during this time when the government started deploying the police and the military everywhere, giving them orders to arrest or “shoot to kill” violators of the quarantine. Many Filipinos criticized the government’s general approach. Soon after, the hashtag #SolusyongMedikalHindiMilitar (medical, not military, solution) became trending because of the government’s refusal to carry out decisive steps to improve the country’s ramshackle healthcare system.

Duterte’s shift from underestimating the dangers posed by the virus to being alarmist about the latter may have contributed to the spread of the virus. In contrast to the sobering and calming speeches made by leaders of South Korea and New Zealand, for example, Duterte’s imprudent statements and rash orders left Filipinos even more dazed and confused. His pronouncements led to people to massing up on highways and streets and panic-buying in supermarkets, in violation of physical distancing measures. The day after Duterte ordered the lockdown, bus stations were crammed as people hurriedly sought to go home to the provinces. Because of ill-planned and disorganized military checkpoints installed in various points of Metro Manila, people, especially motorcycle drivers and pedestrians, were brought dangerously close to each other in massive traffic jams.

A ward dedicated to COVID-19 patients at the Philippine General Hospital. Photo: Wikipedia Commons

Duterte’s policies and rhetoric

Blaming the pasaway fits perfectly well with Duterte’s policies and rhetoric. Crises, it has recently been said, accentuate features of society which have existed even before the crisis, even as they also change other features. The government’s scapegoating of the pasaway during the pandemic is only a continuation, albeit in a heightened and more grotesque sense, of its approach towards the poor.

Duterte’s main campaign promise was to end illegal drugs and criminality in the country within six months after he is elected. His “war on drugs” campaign took the form of killing suspected drug addicts and pushers on the pretext that they had been armed and were resisting arrest, and by means of hitmen riding in tandem on motorcycles. An estimated 30,000 have been killed under the drug war, mostly street-level suspects from the urban poor. The said war was accompanied by a propaganda offensive in which drug addiction in the country was exaggerated and the lives of drug addicts were debased. One radio advertisement said that the mind of a drug addict is worse than that of an animal.

The government’s depiction of the lockdown as being rendered ineffective by the people’s hard-headedness finds its precursor in its repeated declarations that the drug war has failed. In both cases, the root causes are not addressed, so even if measures designed by the government were actually implemented, the problem is not solved. In both cases, failure is used to justify even more violent and draconian measures against the people. On the pretext of the pasaways, the government toys with the idea of imposing Martial Law.

Duterte also waged brutal wars against groups in the country whose members predominantly come from the poor. He intensified the counter-insurgency campaigns against the NPA in the country and tries to crush the progressive organizations he accused of being the rebellion’s fronts. He also engaged Muslim armed groups in the country’s southern island of Mindanao in a war which he depicted as a war against terrorism. In both wars, Duterte refused to examine the historical and socio-economic root causes, choosing to merely demonize the groups. Because of these wars, the police and the military have become very powerful political forces in the country, and these forces have been loyal to Duterte so far.

Duterte’s government has already been described as divisive by many observers, and rightfully so. In its version of “Us vs. Them” populism, it has identified its “enemies,” and has publicly demonized and attacked them in various ways. Only Duterte and his law-abiding followers are believed to be good; the country’s elites (“greedy oligarchs”), the political opposition (“opportunist dilawan”), the mainstream media (“biased”), the Catholic church (“full of pedophiles”), the Left (“communist-terrorist”) and all other political forces are not.

Many Filipinos remain desperately poor. “Duterte refused to examine the historical and socio-economic root causes, choosing to merely demonize the groups.” Manila, Philippines – Homeless Filipino man sleeping at the street. Image: aldarinho / Shutterstock.com

The enemy is not the pasaway, the poor or the rebels

It has been said that changing human behavior is key to tackling pandemics. This was the case during the Ebola epidemic in the Democratic Republic of Congo, where long-practised traditions in burying the dead, particularly touching corpses, were modified to become safer. Indeed, the famous Filipino hospitality and sociability will temporarily have to be tempered. But such cultural adjustments can only do so much. The situation calls for an overhaul not just of social behaviors, but of social systems that reproduce various kinds of health and socio-economic crises.

As the lockdown enters its second month, what is to be expected? If the Duterte government persists in its militarist approach, more deaths. The Philippine health system, the so-called frontline itself, will be completely inundated and unable to cope with the rising number of cases. The number of infected Filipino health workers, which currently exceeds 1,000 cases, will inevitably increase.

The Duterte government will never be able to correctly deal with the pandemic unless it recognizes what, not who, the real enemy is. The enemy is not the pasaway, the poor or the rebels, but problems of a systemic nature which have festered long before the coronavirus reached Philippine shores: an ill-equipped and state-neglected public health system, widespread poverty and hunger among the people, dependence on foreign powers and aid with strings attached, lack of land reform that could have paved the way for the country’s food sovereignty, and the lack of national industries which could have bolstered health-related R&D in the country.

Noreen H. Sapalo & Teo S. Marasigan

Neen is a member of AlterMidya, a network of alternative and progressive Filipino media outfits. She is also a lecturer of culture and politics and a graduate student of anthropology at the University of the Philippines.

Teo is a columnist of progressive publication Pinoy Weekly and author of Na Kung Saan (University of the Philippines Press, 2019), a compilation of essays on popular culture and progressive politics in the Philippines.

* Opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect FORSEA’s editorial stance.

Banner: Antipolo City, Philippines – April 2, 2020: Police officer wears improvised personal protective equipment while on duty during the lockdown or community quarantine due to Covid 19 virus outbreak. Photo junpinzon / Shutterstock.com>/small>